By Professor David Blake, first published by Facts4EU.Org on 04 Dec 2020

© Brexit Facts4EU.Org

The European Union is seeking a ‘level playing field’ with the UK after Brexit. One of the key issues concerning the EU is ‘dumping’. It is worried that the UK will become a super-competitive, de-regulated ‘Singapore-on-Thames’, undercutting the prices of products produced in the EU in the same way China does globally.

In fact the opposite is the case. It is the nineteen EU member states operating a single currency, the euro, that are dumping their goods onto world markets ‒ in particular the UK ‒ because the euro is a structurally undervalued currency.

The scary truth about the euro

The global economic and financial community regards the euro as ‘just another currency’. It is not.

Firstly, it is ‘incomplete’. Unlike every other currency, there is no single sovereign standing behind it. Each member state stands behind the euro only to a certain percentage and collectively the member states do not share joint-and-several liability for each other’s national debts. This makes them ‘sub-sovereign’ members of the Eurozone (EZ).

This is very different from what happens in fully sovereign states, like the UK and US, where their central banks and Treasury departments stand fully behind the bonds issued by their governments and can, if necessary, print enough money to pay off their national debts. The European Central Bank does not have the legal power to do this.

Secondly, it is an artificially-constructed currency, as a consequence of the fixed rates used in 1999 to convert the domestic currencies of EZ members into euros. This affected not only the internal exchange rates between the EZ members, but also the international value of the euro.

The net result has been a downward bias in the international trading value of the euro, with the inefficient southern member states dragging down the value of the euro relative to what it would be if all member states were as efficient as Germany and the Netherlands.

How the artificially-undervalued euro has damaged the UK

The euro is undervalued against sterling on a purchasing power parity (PPP) basis and has been all of the time since its introduction. The UK has almost always run a trade deficit with the EU over the period of its EU membership, but the deficit worsened considerably after the euro was created.

In 2019, the UK’s trade deficit with the EU was £73bn and the ratio of exports to imports was only 80%: for every £1 of goods and services we buy from them, they only buy £0.80 from us.

We know that Germany is desperate for a trade deal with the UK

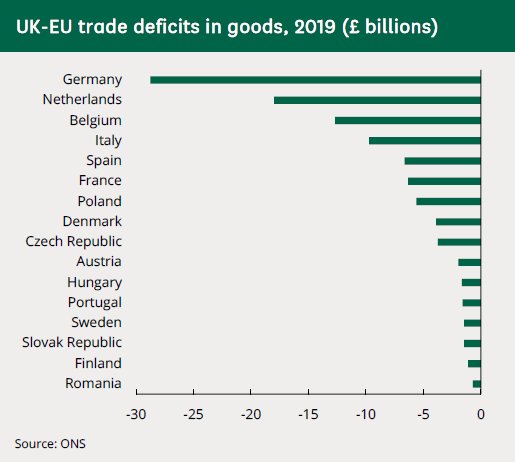

Looking at its massive trade surplus with the UK we know why. The chart below shows that in 2019 the UK had a trade deficit in goods with 16 EU member states. Germany leads the list with £29bn, mainly in automobiles. Even allowing for potential quality differences between British and German cars, a key explanation is again the undervaluation of the euro. Germany’s trade surplus is, of course, our trade deficit.

© House of Commons Library: Research briefing 10 Nov 2020, ‘Statistics on UK-EU Trade’

If the UK maintains the close economic ties with the EU that the EU wants, the UK will remain a captive market for German and other EZ member goods and will be unable to address the structural disadvantage which it finds itself in.

The UK could impose an anti-dumping duty of over £65bn on the protectionist EU

The euro is undervalued against sterling by 15-20% on a PPP basis. Had the euro been correctly valued, then EZ exports to the UK in 2018 would have been lower by between £67.2bn and £88.4bn. The UK would therefore be entitled to impose an annual anti-dumping duty on the EZ in this range.

The EU is following a classic ‘beggar thy neighbour’ strategy. This is where a country or trading bloc follows a protectionist trade strategy that adversely affects its trading partners.

Typically, this involves tariffs and quotas, but in this case the EU’s weapon is a structurally undervalued currency.

Part One of a two-part article by Professor David Blake